Dr John K Pinnegar, director of the International Marine Climate Change Centre, Cefas presents an overview of the complex implications of the changing climate for fishermen

With the UK experiencing some of the warmest weather on record, powerful images of parched landscapes and devastating wildfires have been a stark reminder that the impacts of climate change are being felt all around us. But what about the impacts that are less obvious? What do we know about the impact of climate change in our seas, and for the people who rely on them?

At this year’s annual scientific conference of the Fisheries Society of the British Isles in July, I was asked to give the highly prestigious Jack Jones Lecture for 2022 on the topic of ‘Climate change and the future of fish and fisheries’.

Climate change can affect fish and fisheries in different ways. It can have direct and indirect consequences for habitats or the distribution of predators and prey. It can affect the fish directly by impacting growth rates, reproduction or migratory behaviour. It can have knock-on consequences for fisheries through changes in ‘catchability’ or safety at sea, and hence it can determine what species are available to consumers, or even the price of fish on markets.

One of the most widely discussed impacts of climate change is the effect on the distribution of fish stocks. Many studies show the poleward redistribution of commercial fish stocks, and this includes those of importance around the British Isles. These studies have often made use of fishery-independent survey datasets, such as those collected on an annual basis by Cefas, ABINI and Marine Scotland Science.

These show that: (1) 70% of the fish species around the British Isles have responded to warming by changing distribution and/or abundance; (2) the distribution of species has shifted by distances ranging from 48km to 403km over the past 30 years; (3) species found in the North Sea have generally been found at greater depths – around 3.6m deeper per decade.

In general, pelagic species such as sardine, anchovy and mackerel (but also squid) have moved faster and further than demersal species, with an increase in warm-water fish such as red mullet and anchovy, but also observed declines in cold-water species such as wolffish and cod.

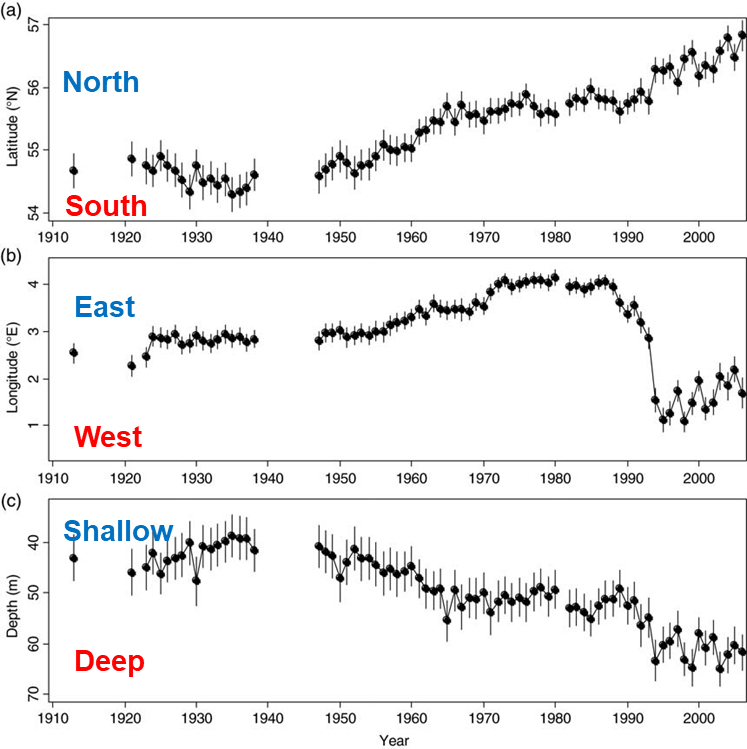

These long-term trends are also apparent in datasets derived from commercial landings. Cefas scientists, led by Dr Georg Engelhard, have published a series of scientific papers based on an analysis of port landings as far back as 1913. Cefas has digitised more than 37,000 maps of recorded monthly fishery landings in the North Sea. From this work, we can see that plaice catches were predominantly found in the southeastern part of the North Sea for much of the 20th century, but have shifted northwestwards towards the Dogger Bank and central North Sea, as well as into deeper waters around Orkney and Shetland (see diagram below).

Over the last decades, the centre of the North Sea plaice fishery has shifted in a northwesterly direction, and into deeper waters. (Graphic: Engelhard et al, 2011)

Similarly, throughout much of the 20th century cod catches were obtained throughout the whole North Sea, but in recent decades, large catches have only occurred in deeper and therefore cooler waters in the northeastern part, around the Norwegian Trench. These observations correlate with rising temperatures, but also with intensive fishing pressure in the southern part of the North Sea.

What can these trends tell us about the future of fisheries and fish stocks? Globally, climate change is shifting the distribution of shared fish stocks between neighbouring countries’ jurisdictions. This can have significant consequences for quota allocation, fishery access and increased steaming times. A recent modelling study suggested that by 2030, 23% of transboundary stocks will have shifted and 78% of the world’s exclusive economic zones (EEZs) will have experienced at least one shifting stock.

This has the potential to impact quota allocation and management, something that we have already witnessed with the redistribution of mackerel in the North Atlantic after 2006 and subsequent disagreements between Iceland, Faroe Islands, Norway, the UK and the EU about permitted catch levels.

Climate change will create both winners and losers in the fishing industry. In February, we featured the final trip to sea by Chris Pepper, who worked the last of the Cleethorpes fleet of beach- launched vessels that targeted cod during the winter months. The lack of cod has put the fleet out of business (Fishing News, 10 February, ‘Humber cod: The end of the line’). (Photo: John Worrall)

In the UK, Cefas scientists have been attempting to predict the future productivity of stocks using a wide range of sophisticated computer models, driven by climate change projections from the UK Met Office. The consensus is that climate change will result in both opportunities and threats to the UK fishing industry.

In the UK EEZ, it is predicted that black seabream, seabass, pilchard (sardine), anchovy, red mullet, sole and cuttlefish will all become more common, whereas saithe, lemon sole, ling, cod, haddock, megrim, halibut, wolffish and herring may suffer a decline in suitable conditions.

Climate hazards and risks

An additional risk of climate change is increased occurrence of extreme events, such as storms or heatwaves. Projections regarding future storminess remain highly uncertain, and although meteorologists agree that storm frequency seems unlikely to change in the coming century, the severity both in terms of wave height and wind speed is likely to increase.

These storm events pose a direct risk to fisheries by disrupting fishing effort and increasing the risk of physical danger to fishers, their vessels and gear, as well as to coastal infrastructure.

In 2021, researchers from Cefas, working with scientists from Denmark and the Netherlands, published a ground- breaking climate-change risk assessment in which 380 fishing fleets covering 105 coastal regions across Europe were scored in terms of their sensitivity to the impacts of climate change.

There were significant differences in climate risks depending on gear types, in which dredgers were scored as the most sensitive. Fleets using pelagic and demersal trawls together with purse seine fleets had the lowest climate risks, primarily due to the low sensitivity associated with the species on which they fish.

Coastal regions in northeast England and southern Scotland were identified as some of the most ‘at risk’ in Europe, primarily because of the vulnerability of stocks combined with low catch diversity. However, fisheries in northern Scotland and the South West of England were assessed as less vulnerable.

The benefits of future science-industry collaboration

With a wide variety of challenges facing fishermen around the British Isles, adapting to the impacts of climate change will be vital. This could include creation of alternative employment opportunities, or provision of economic ‘safety nets’ through wider social measures. In other regions, increasing efficiency and catch diversity should be a priority.

Closer collaboration between scientists and industry, such as work undertaken by Seafish, Cefas and the UK Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership on the impacts on UK seafood supply chains, can help develop solutions that can both protect fish stocks and support livelihoods.

For example, as part of the Seafish Watching Brief series, available on the Seafish website, the partnership has considered recent advances in scientific understanding, as well as on-the- ground industry experience of climate change drivers and impacts throughout 2020 and 2021.

If you are interested in our work, please click here.

This story was taken from the latest issue of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.