For three decades, the East Anglian herring fishery’s highest accolade was the award of the Prunier Trophy. John Worrall gets a first-hand account from a spare hand

The crew on the Silver Crest at Lowestoft in 1956: Rodney Forster on the right in the light sweater, then behind him ‘Speedy’ and Bobby Banks. Then the four in the middle, right to left: Jimmy Aldiss, skipper Arthur Utton, Fred Crisp and ‘Poley’. Bottom left is Richard Winney, with Arthur Aldiss next to him, then the skipper’s son, also Arthur Utton, and the cook, Voldenor Kemp, bottom right.

It was a mix of marketing ploy and revival strategy. Madame Simone Prunier was the daughter and granddaughter of restaurateurs who, in turn, ran their famous Paris establishment and, in turn, died young, so that in 1935, at the tender age of 22, she found herself running the show. But she and her husband more than rose to the challenge. They branched out by opening in London’s St James’ Street.

There she heard of the parlous state of the East Anglian herring industry. Catches, though still substantial, had been in steady decline since the pre-First World War peak, as the increased efficiency of steam and then diesel power ate into stocks.

More particularly, tastes had changed. The ‘king of fish’ – oily, nutritious and much rated by gourmands for its versatility and, on the Continent, for the pickled version – had lost domestic appeal because its boniness didn’t go well with batter and chips. First-sale prices were fluctuating to the extent that catches occasionally went straight for fishmeal.

“Sacré bleu!” exclaimed Madame (allegedly). The fish of the East Anglian autumn ‘home fishery’ was of the same spawnfilled excellence, but the problem was consumer attitude. Something had to be done.

The fact that his grandfather was well-known skipper Arthur Durrant got Rodney Forster his first fishing job…

She decided that a profile resurrecting annual competition was the thing, with a slap-up meal down in St James’ – transport provided – and a cash prize of £25 for the skipper and crew of the drifter – Scottish or English – who landed the biggest single catch to Lowestoft or Great Yarmouth. There would be a runner-up, and if the winner was English, the runner-up had to be Scottish, and vice versa.

Sculptor Charles Sykes was commissioned to produce a trophy in Purbeck marble – a hand rising from a wave grasping a herring (but was the hand waving or drowning?) – onto which the size of the catch and name of the winning boat and skipper would be engraved. For the boat, there would be a weather vane in the shape of a herring, with the year emblazoned upon it, to be fixed to the fore or mizzen mast.

The first competition ran in the autumn of 1936 and was won by Boy Andrew BF 592 with 231 crans, with Frons Olive YH 217 as runner-up with 224¼ crans, both landing to Great Yarmouth.

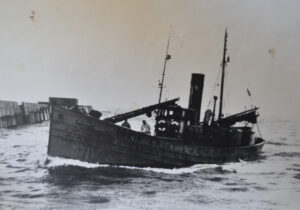

… on Silver Crest, seen here coming into Lowestoft.

One Fishing News reader who got the St James’ treatment as part of a winning crew was Rodney Forster. He was spare hand on the Silver Crest LT 46, under skipper Arthur Utting, which in 1956 was joint winner with the Stephens FR 156, both boats landing 215½ crans, one to Lowestoft and the other to Yarmouth.

“We got that shot only 16 miles off Lowestoft,” he says. “We could see the Ness light going round. We’d seen gulls sitting on the water – the water was white, creamy – and we shot at 5pm, either 91 or 97 nets, can’t remember, but each 22 yards long – and then we went for tea. But within an hour, the buffs were logied – they were going under with the weight of fish.

“I was on watch, and I said to the skipper: ‘Our buffs are logied, bloke.’ We called the skipper ‘bloke’. And he said: ‘What are you talking about?’ Then he looked and said: ‘Well, we better have a look on…’

A photo of Simone Prunier from a 1960 Fishing News profile, which begins: “Combining the wisdom of Solomon, the generalship of Napoleon, the business acumen of a Rothschild with a charm that is all her own, Madame Prunier presides today over a seafood empire that is unique.”

“So we started hauling at 6pm, and didn’t finish until 3pm the next afternoon. That’s how long it took to get them in. There were so many herring that the middles just dropped out of most of the nets. They couldn’t take the weight once the herring had died. The whole fleet was spoilt.

“My hands were all bleeding. The capstan did the real heavy hauling, but then you’ve still got to get the net full of fish over the side. We’d pull them over. The men had to do that – it was one, two, three and then boom – you’d haul about four or five inches at a time, trying to get the fish over the side, and the net would run and run, and you’d be shaking the fish out.

“There were other boats out there, the Scottish fleet, everyone, but they didn’t get anything like that. We just happened to hit a shoal, or a shoal and a half, really. You’re talking hundreds of tons. If we had got every herring, we’d have filled three boats. And yet we still won the trophy with what we did get.

“And when we got in, we started to unload, but we were knackered, and they got some other men from somewhere to do it. And we had to have a new fleet of nets put aboard.”

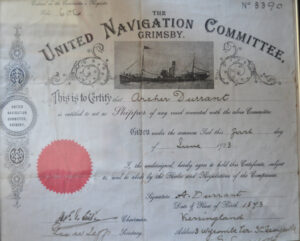

Rodney came from a fishing family. He had seven brothers and a sister, and all the brothers went to sea. More particularly, his grandfather, Archie Durrant – who himself had 14 kids – was a famous Lowestoft owner and skipper. Rodney didn’t go straight to fishing, because his first job, aged 15, was with builders’ merchant Jewson. But that didn’t work. “I was there a week in all the sawdust… I thought: ‘I ain’t doing this.’”

He’d already done one fishing trip on a steam drifter called Advisable, because his neighbour was chief engineer. He’d been sick as a dog, but still fancied the job.

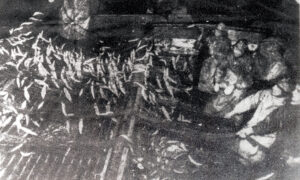

Hauling a big shot was long and laborious. It took the Silver Crest crew 21 hours to get 215 crans aboard.

“So I went to where all the company offices were in Lowestoft, and saw a note saying: ‘Spare hand wanted, Silver Crest’. I asked in the office, and they said: ‘You’d better go down to Kessingland and see the skipper.’

“So I cycled down and knocked on his door, and he come out the bedroom window – he’d been on the beer. And I said: ‘I see you want a spare hand.’ And he said: ‘How old are ya?’, and I said: ‘Fifteen.’ And he said: ‘He ya been to sea?’, and I said I’d had a trip on the Advisable. He said: ‘He ya got a fishing family?’. I said Archie Durrant was my granddad. And he said: ‘That’ll do for me.’

“I had to go to the Yarmouth stores to get my equipment, and you got it on the knock, and the office paid for it out of your wages. We left Lowestoft heading for a 13-week trip fishing out of Aberdeen and Shetland, and it was a steam boat and all gas carbide lamps, and did that stink. And there was a gale of wind – I was so sick it were unreal. We called in at Hartlepool for shelter.”

A readers’ photo entry from 1952 depicting a North Sea herring fisherman.

The Silver Crest LT 46 was slightly unusual in that she was a steam boat that had been converted from diesel. She’d been the Larus LT 381, built in 1928 at Selby with a 210hp three-cylinder Plenty diesel, but the engine performance was poor, and in 1929, an Elliott and Garrood triple-expansion steam engine was fitted and she became Silver Crest. She was the last steam drifter to win the trophy.

Rodney said: “I was spare hand, and did whatever needed doing. I’d be stowing the buffs at the end of the haul, and cleaning herring for the crew to eat. When you’re herring-drifting, you get a few whiting because they chase the herring, or the odd cod, and they made a change from herring for breakfast. I used to have to clean 100 herring a day, doing that while the others all tidied and put away. That’s how many they used to eat.

The Silver Crest crew, all scrubbed up, with Madame Prunier at her London restaurant – Rod Forster, second right, looking particularly well scrubbed.

“Or I’d be down boxing the herring. When the net came over the side, they’d shake the fish into the kid – the deck area in from the rail – and into a hole down to the bunker chute, and there was a door at the bottom which you’d lift and let them pour into a box, then shut the door and get another box, and so on.

“I’d be stacking them up to 10 boxes high, about four stone in each. There was a knack in doing it. We’d take 10 or 11 tons of cobbled ice to Aberdeen, all in different compartments of the hold. We used to have to chop it with an axe because it used to go hard on the outside, but inside it was all loose. You’d get a row of boxes of herring and fling ice all over it, and then you’d start again.

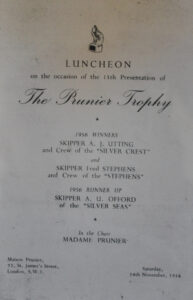

It was a posh do, with the winners named on the menu, which of course included herring (note the runner-up was the Silver Seas, also owned by Arthur Catchpole, the Silver Crest’s owner).

“If you’d filled your boxes, we used to run the herring loose in the wings. And then back in port, you’d have to scutcher them out to unload, shovel them into baskets. But you only needed four baskets, because you’d swing them ashore and swing them back empty. But we’d have 400 to 500 boxes onboard, aluminium, six to a cran. And four baskets to a cran.

“And those Scotch girls ashore used to gut one a second, and get a shilling a bushel. They used to bind their fingers with rags because they’d be sore with the salt.

“But I also had to go down into the bunkers when the stoker couldn’t reach the coal and I had to shovel it along. They used to open the bunker lid up and drop me in, with a shovel and a little carbide duck lamp, and then screw the lid down. You’d be down there five or six hours. And all you wore was a pair of pants.

“Two hundred miles out in the Atlantic in a gale of wind, the coal would be chasing you round. I used to use my hands on the big lumps. And when you came out, there was no sink or showers or nothing, and you’d have a bucket of water, and you’d cut a lump of Chester’s carbolic off and wash yourself, and the chief used to pour the water over your head. There was a lot of dust down there. That’s why I’ve got COPD.

“Once I’d learnt to scud a net and haul, I went up the order to three-quarter half-quarter, which meant I got seven-eighths of a share of the profit, there being 11 shares for a crew of 11. But we didn’t make much money at the herring.

The 1956 joint winning skippers were each presented with a weather vane by Sir Lennox-Boyd, secretary of state for the colonies – Arthur Utting of Silver Crest to the right, Fred Stephens of the Stephens to the left.

“The owner, Arthur Catchpole, had two boats the same, the Silver Seas and Silver Crest, but even though we landed all them herring, at the end of the season we hadn’t earned enough to pay for the coal. So he pulled me to one side and give me £2 10s, and this other man stood there with his peaked cap who had about six little kids, and he give him a fiver.

“After that 13 weeks off Scotland, we’d come back to Lowestoft, and for the next fishing we’d go off the Humber, because the herring were moving south, and then down here off East Anglia for the home fishing.

“I was about a year and a half on Silver Crest. After Christmas, when all the herring had disappeared, we used to go round to Milford Haven, longlining for skate and conger, and off Holyhead, going in and out of those ports. And we fished Morecambe Bay, landing into Fleetwood.

Stephens FR 156, joint winner of the 1956 trophy, was diesel powered, while Silver Crest was the last steam drifter to win the trophy.

“After Silver Crest, I went on the Henrietta Spashett LT 82, with Richard ‘Roscoe’ Fiske, son of the legendary Jumbo Fiske. Again we went to Aberdeen, in and out of there and Shetland. Then, after the home fishing, we put winches and spars on and went fishing out of Morecambe Bay – at least until the Dutchmen came with about a dozen huge beamers that towed anchor chain-mats quicker than we could steam.

“We also fished off Trevose Head near Padstow, and you’d find bedsteads and old cars that the mud dredgers used to dump. But the Dover sole were amazing.

“On my last year of herring fishing, I worked on the Dauntless Star LT 367, with Georgie Draper as skipper, and he won the trophy in 1959, although I wasn’t with him then. But we broke the Lowestoft port record in 1960, because in 10 weeks we earned £10,000, and I picked up £80. And I got married with 100 guests, and they were all saying: ‘How can he afford this reception at ten bob a head?’ And this Scotsman said: ‘He’s with Georgie Draper, and he must have picked up 80 to 100 quid.’

The Prunier Trophy, ‘sculpted in Purbeck marble by the late Charles Sykes’, in the words of the 1952 Fishing News caption writer. “It depicts a fisherman’s hand holding a herring. The base of the statuary merges into a symbolic wave.”

“Then I went trawling for a year or two from Lowestoft. I was on the ‘Queen’ boats – Ormseby Queen, Wroxham Queen, Runham Queen – owned by the Heptons, father and son, although the boats were crewed and paid through Boston Deep Sea Fisheries. And didn’t those boats roll. They were all top-heavy. Even in a flat calm, they had a lazy roll that put the rails under. And in a gale of wind, well…

“But they weren’t so bad when you got a bit of fish down. We used to do 12-day trips – Dogger Bank, off Norway, all over the place. As second engineer, I got one pound and ninepence in the £100 that the boat earned. If we made £1,000, I got £11, for a 12-day trip. Nearly £1 a day – that was good money 65 years ago.”

But eventually, Rodney left the fishing for a while. “I finished in ’63, because my little boy Mark came along, and I’d hardly known my dad. We hardly saw him, and that weren’t no life for a woman with kids.”

He first went to the Birdseye factory in Lowestoft, and later on the docks as a seasonal worker and then crane driver, unloading timber at Boulton Paul.

“But then I bought a fishing boat, a longliner, an Offshore 27 with a 350hp engine, which could cruise at 27 knots and work up to 60 miles out of Lowestoft. I had a crew working it and I sold the fish, later with a mobile shop, working around Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire, staying some nights with my brother in Luton.”

He eventually sold his fish round to his brother, and spent the last part of his working life as the landlord of two pubs, the Royal Standard in Lowestoft, where he got the Innkeeper of the Year award, and then the Ark Royal in Wells.

And the Prunier Trophy? It ran out of steam not long after Rodney left fishing. There was no landing submitted in 1965, and it was awarded for the last time in 1966, when the winning catch, by Tina Ros FR 346, was down to 128 2/3 crans.

But by that time, Madame Prunier had handed the trophy to the Herring Industry Board, which subsequently held the award ceremony in Yarmouth or Lowestoft town hall. She’d done her bit.

This story was taken from the archives of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.