Plymouth-based scientist Richard Kirby, a plankton expert, looks at the links between bluefin tuna and water temperature, and suggests that climate change may disrupt the historic cycles that have driven tuna migration in the past

Atlantic bluefin tuna have returned to UK coastal waters after an absence of over half a century. Their reappearance in UK seas (and also further north and east) makes an interesting story, as their presence is symptomatic of the changes in the distribution of many marine animals around UK coasts due to recent warmer sea surface temperatures.

Bluefin tuna are one of most exploited fish species on earth. As a result of commercial exploitation in the Atlantic, bluefin tuna declined in abundance from the 1960s to the mid-2000s, to the point when the animal became an IUCN Red List species.

Stringent action by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) has contributed to an improvement in stocks in the last decade and, as a result, the Atlantic bluefin is no longer on the Red List. However, the recovery in bluefin abundance is not the main reason for the reappearance of Atlantic bluefin in UK seas.

I am a plankton scientist interested in the marine food chain, from the plankton to fish and seabirds, and in how this is affected by the environment and fishing. I am at sea regularly sampling the plankton off Plymouth, and this is where I increasingly noticed bluefin tuna breaking the surface in the early 2000s.

I was naturally interested in what had brought this fish back, and whether their reappearance was another symptom of the climate-related changes in our seas that my long-term colleague Gregory Beaubgraned (Lille University, France) and I were reporting. We therefore began a study into the reappearance of bluefin tuna, led by our post-doctoral researcher Robin Faillettaz (now at IFREMER, France), and published the results in 2019 in the journal Science Advances.

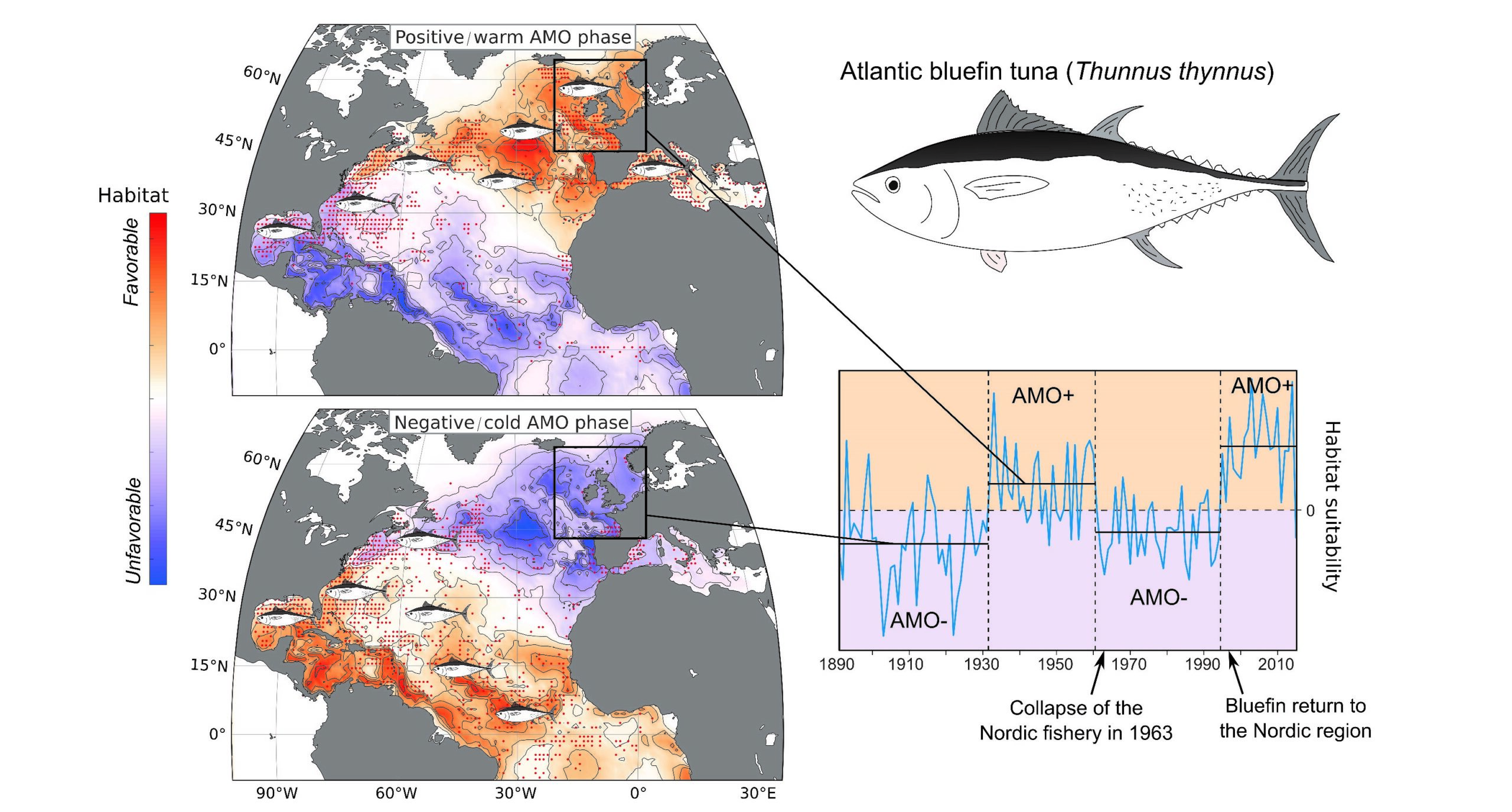

Our 2019 paper found that a switch between negative (cool) and positive (warm) phases of a climatic cycle called the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) over the last 400 years had a major influence on bluefin tuna distribution. It created a seesaw- like northerly advance (during a warm climate phase) and a southerly retreat (during a cool climate phase) of bluefin tuna in the North Atlantic.

The most striking example of this effect was the sudden collapse of the Nordic bluefin tuna fishery in 1963. The collapse coincided perfectly with the most rapid known switch in the AMO from its highest to its lowest recorded value in only two years.

After that switch, bluefin tuna also vacated the North Sea, and the following cold decades saw the famous North Sea gadoid outburst; cod is a cold-water species, and the cooler water in the North Sea led to an increased abundance of cold- water plankton favourable to the recruitment of larval cod.

Conditions remained unfavourable for bluefin tuna in the northern Atlantic until the late 1990s, when the AMO re-entered the current warm phase and bluefin tuna once again started to reappear around the UK.

We have now entered the warm phase of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation cycle, resulting in bluefin tuna moving into the North Atlantic – but climate change means that the formerly predictable shift back into a cold phase in the coming decades is now in doubt.

Our story about the reappearance of Atlantic bluefin tuna is not over, however. New studies on the climate in the North Atlantic region have shown that the AMO is not a reproducible North Atlantic climate cycle. Instead, the climatic cyclicity was an artefact of several warming and cooling factors that appeared to give a long-term cyclical effect; notably, the AMO is due to volcanic eruptions and ocean circulation rather than solely regional, internal climatic forces.

While these new studies don’t alter our findings that the distribution of North Atlantic bluefin tuna responds to climate- driven sea temperatures, they alter the expectation of a predictable climatic cycle, and that climate conditions will inevitably reverse and cool, and bluefin tuna will retreat southwards once again. This time, bluefin tuna may be here to stay if, in the absence of other counteracting climate- influencing effects, global climate change causes sea surface temperatures to remain warm.

The current climate-driven warming of the North East Atlantic that caused the northwards movement of bluefin tuna has implications not only for the future distribution of bluefin tuna but also the biology of the region. Further down the food chain, in the plankton where the food chain begins, North East Atlantic copepod communities, which are the food of larval fish, have shifted northwards by over 10° latitude in the last 50 years.

Warm-water fish species like bonito are now caught around the UK (the first report being a bonito caught in the North Sea in 2010); gilthead sea bream are caught frequently; red mullet have increased dramatically in abundance off Scotland, first reappearing in 1995 after an absence of 70 years; and cold- water fish like cod have declined in abundance in the North Sea. On the seabed off Cornwall, spiny lobster, a southern warm-water animal, is currently increasing in abundance, and in 2022, unprecedented numbers of the warm-water common octopus were reported by Cornish fishermen.

In 1988, my PhD supervisor, the UK geneticist RJ Berry, opened his presidential address to the British Ecological Society with the sentence: “The fundamental problem in ecology is: ‘Why is what where?’”. (His second sentence was: “We is not the main reason for the reappearance of Atlantic bluefin in UK seas seem to have made rather slow progress in answering this since the British Ecological Society was founded in 1913.”)

It is just as fundamental to understand ‘why is what where’ in the sea if we are to manage fisheries such as bluefin tuna well, but we continue to not ask that question or to be concerned by it, often assuming that an increased local presence is simply due to an increase in a total abundance that can now be exploited.

The recent tragedy that has befallen North Atlantic mackerel stocks is a warning of the consequences when we fail to quickly understand ‘why is what where’ and respond appropriately to changes in distribution. Mackerel has moved northwards due to warmer temperatures, and its unregulated exploitation in new regions has led to its overfishing as the politics of quota distribution fail to keep pace with the changed movement of the fish stock.

Clearly, I believe that the management of exploited fish stocks should always consider the environment, but how do we integrate environment and fishing to manage the exploitation of a wild, mobile species effectively?

In a recent study that we hope will improve fisheries management and fish conservation, we developed a new model called FishClim that integrates the effect of fishing and climate to mitigate their effects and the inevitable knock-on effects on the ecosystem. We developed our model for North Sea cod, but it is applicable to any commercially exploited species.

In the context of climate change, a model like FishClim is essential to establishing fishing quotas so that we can exploit fish stocks sustainably without precipitating their rapid collapse.

This story was taken from the latest issue of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.

Sign up to Fishing News’ FREE e-newsletter here.