The Scottish port of Eyemouth suffered Britain’s worst-ever fishing disaster when 189 men and boys perished on what locals still call Black Friday. Brian W Lavery recalls the tragedy

Eyemouth’s fishermen were renowned as takers of great risks and getters of great rewards.

A contemporary etching showing the heroic struggles in the raging seas off Eyemouth during the 1881 disaster.

With the 19th century’s industrialisation and a cheap and plentiful supply of fish, people flocked to this Scottish east coast town. Its population grew from 500 to 3,000. Eyemouth was booming.

But all through the spring and summer of 1881, ferocious storms battered the east coast, so that even Eyemouth men dared not leave port. For days and weeks on end across that period, their vessels remained tied up.

So when a calm day dawned, the fleet decided to take its chance. There may have been those who thought better of it, but the tradition in Eyemouth was that if one boat was going out, all went out.

But on Friday, 14 October, 1881, the brave men of this east coast fishing port took one risk too many.

Eyemouth harbour, pictured in 1840.

There were two warnings – one that they did not heed, and one about which they knew nothing.

The pier-head barometer – which had often been ignored in the past – forecast a sudden change for the worse in the weather. And in the local post office, a telegram warning of gales coming their way arrived too late.

Postmaster John Campbell McRae received the telegram from Yarmouth, where 56 Eyemouth men had been fishing in Norfolk for the late herring.

But even if he had rushed it to the pier – which he did not – he would not have been able to get the message delivered in time.

The harbour at Eyemouth as it looked shortly before the tragedy.

As the men of Eyemouth put to sea, many other Scottish ports like Dunbar, Anstruther, Fraserburgh and Wick stayed put. But it was more than just doggedness that made Eyemouth’s fleet sail into a terrible fate that Friday. The men were driven as much by economic necessity as they were by courage.

For unlike those other ports, they had not received huge grants and investment from the Fisheries Boards and Whitehall, despite being one of the biggest fleets in the country.

Although fishing ports up and down the east coast had received government aid to improve their harbours, the port at Eyemouth remained dangerous.

Another reason lay with the kirk. The Church of Scotland had claimed a ‘tithe’ (one-tenth) of the men’s income for many years.

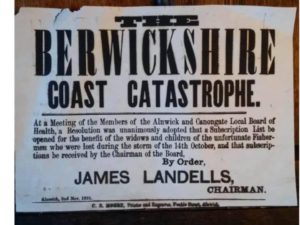

Fundraising took place nationwide for the victims of the disaster – this poster from Alnwick tells of a new subscription being opened for ‘the widows and children of the unfortunate fishermen’.

After a fierce campaign led by Eyemouth fisherman Willie Spears, it was agreed that the men could ‘buy out’ the tithe for £2,000. It was not until 1878 that the loan the men took out to pay the kirk was cleared.

With that background, the spring and summer storms of 1881 and the hunger of their bairns, it is clear why the men ignored the barometer.

The Times of 25 October, 1881 reported: “The storm signal was also hoisted, and so far there had really been some warning given of the impending strife. It is even said that the harbour master cautioned the fishermen against going out.

“But the men had been lying in enforced idleness for a few days, and many of them were anxious to earn a few shillings for their families.

“Besides, the fish were known to be plentiful near the coast; and tempted by the prospect of large hauls, and trusting their reading of the sky rather than the barometric indications, the fleet of handsome decked fishing boats put out to sea.”

That gamble was to have catastrophic consequences. A survivor later told the Times: “The storm and darkness came on like a clap of the hand.” Hurricane-force winds, lashing rain, looming dark clouds and massive waves caused chaos.

The tempest struck at noon, and as the Eyemouth fleet tried a dash for home, many of the open-decked sailing keel-boats foundered in mountainous seas in sight of the families still ashore. They could only watch helplessly as some of the boats were smashed to pieces on the rocks as they tried to reach the harbour.

A total of 189 men and boys, many of them from the same families, perished that day. Black Friday ripped the heart out of Eyemouth.

The storm left behind it 93 widows and 267 fatherless children.

Of the 189 who died, 129 were from Eyemouth, 24 from Burnmouth, 11 from Cove and three from Coldingham, all nearby.

But on the Sabbath that week, as a memorial service was being prepared, one of the vessels thought to be lost made a dramatic return.

The Eyemouth memorial to those lost in the 1881 disaster.

The Times reported: “About six o’clock yesterday [Sunday] morning, while but a few people were stirring, the Ariel Gazelle came into harbour, with her crew of seven men all safe.

“They had been at sea for about 40 hours, and had been blown as far as the Dogger Bank, a sandbank in the centre of the North Sea, intermediate between the shores of England and Denmark.

“On reaching port the men were almost completely exhausted by cold and hunger.”

It was said that the boat’s skipper had to have his hands prised from the tiller. The crew had to be helped off the vessel. As they climbed gingerly onto the ladders and then onto dry land, they were mobbed by a surging crowd. They were taken to a local pub to be revived.

One crewman later said he was ‘ashamed to be safe and sound’ as he ‘passed among those women who had hoped that our boat would have proved to have been their husband’s or their son’s boat’.

The skipper, Alex Burgon, was later chief mourner at the funeral of his son John, who had perished on the sail-keel Harmony.

The memorial to the tragedy at St Abbs.

Newspapers were late in covering the story as many of them failed to get their ‘news parcels’ because of trains being delayed by gale damage that swept the country.

But soon the whole country had heard of the disaster and a public subscription was set up. Across the country there were fundraising concerts and sports events.

Local authorities from fishing and non-fishing towns contributed. Even Queen Victoria sent £100 to start the fund – equivalent to a lot more today.

The original appeal for £25,000 was more than doubled to around £50,000. Money came pouring in after the Queen’s donation, ranging from companies sending large cheques to a shilling – ‘a widow’s mite gift.’

The Ariel Gazelle’s surprise return led to local men holding watches for weeks to come, and Royal Navy ships scouring the sea from the Tyne to Montrose.

The hope of ‘stranger things happen at sea’ was stretched to the limit – but there were to be no further miracles.

Representatives from the children’s charity Quarrier’s Homes came to Eyemouth and offered to take those children orphaned on Black Friday, only to be told in the firmest of terms that: “We’ll keep oor ain bairns for the sake of oor future.”

Today, there would be teams of counsellors and other support services to help ease the searing pain of those who lost their loved ones on that day – but they had to carry on as best they could.

There was monetary help and sympathy from all over the country, but the community had to heal itself, as all communities like this had always done.

Some did not survive. There was a report of one woman so overcome that she died of grief a day after the storm. Willie Spears, the man who led the campaign against the tithe to the kirk, was ashore when the disaster struck. He fell into alcoholism and severe mental illness, gave all his money away to the widows and orphans, and destroyed himself with drink.

Some did not survive. There was a report of one woman so overcome that she died of grief a day after the storm. Willie Spears, the man who led the campaign against the tithe to the kirk, was ashore when the disaster struck. He fell into alcoholism and severe mental illness, gave all his money away to the widows and orphans, and destroyed himself with drink.

But for others, life had to go on. Just 17 days after Black Friday, the Eyemouth fleet – fewer by 19 boats and 129 men – took to the sea again.

They were led out by the Ariel Gazelle.

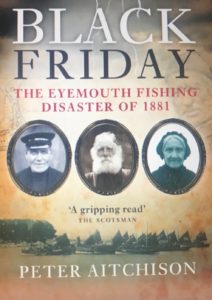

The writer wishes to acknowledge the kind assistance of Peter Aitchison, author of Black Friday – The Eyemouth Fishing Disaster of 1881 (Birlinn, 2018) and that of the good folk of the Eyemouth Past Facebook group.

All photos and illustrations courtesy of Peter Aitchison, Joyce Gunn Cairns and the Eyemouth Past Facebook group.

This story was taken from the archives of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.