Why a Scarborough trawler was driven onto the rocks in September 1976 remains a mystery. Brian W Lavery retraces the night she perished – and the incredible rescue mission that followed

The eerie outline of what remains of the wreck of the trawler Admiral von Tromp. (Photo: John Paulin).

After 46 years aground, her petrified wreck is like a sculpture silhouetted against the seascape. At dusk, there is a gothic air to it.

These days, tourists come for pictures of the remains of the Admiral von Tromp, the Scarborough trawler that was apparently deliberately steered to her doom off the Yorkshire coast.

The rocks that hold what’s left of her fast could double as a film set for where Bram Stoker’s Dracula washed ashore.

Like his ship, the Demeter, the Admiral von Tromp was driven aground on a wild, stormy night off Whitby.

(When Bram Stoker visited Whitby in 1890, he would have heard of a Russian vessel, the Dimitry, which was wrecked offshore. It is thought this was the source for the Demeter.)

And like the wheelman in Stoker’s classic, the man who smashed the trawler aground did not live to tell the tale.

The fictional vessel and the tragic trawler have since both entered into local lore.

At 1am on 30 September, 1976, Scarborough pier-man Walter Sheader was on duty to help the crew of the Admiral von Tromp cast off.

The stricken vessel, photographed on the day of the rescue.

Her skipper Frankie Taal – a widely respected fisherman with more than 23 years’ experience – told Sheader they planned to head 45 miles north-north-east of Scarborough to Barnacle Bank, where the five-man crew intended to fish later that day.

John ‘Scotch Jack’ Addison was at the helm. Originally from Portsoy, in the northeast of Scotland, he had lived in Scarborough for years and was married with a baby daughter.

Sheader noted that the crew were all in good spirits. There was nothing untoward as the 46t fishing vessel cast off.

Engineer Tony Nicholson took his place in the engineroom, and the skipper and John Addison were in the wheelhouse.

Mate Alan Marston and deckhand George Eves headed to the galley.

Skipper Taal told Addison he was going to have a coffee with the lads below and would be back to check things later. Addison nodded, and the skipper left for the galley.

There was a force three easterly and some heavy fog, but this was of little account as they were heading away from the coast. The sea was slight, and there was a heavy onshore swell.

Visibility was down to about 40 yards, but the Admiral von Tromp was a modern vessel with the latest navigational aids.

About an hour or so out to sea, Skipper Taal returned to the wheelhouse as promised. Addison seemed content to stay at the helm.

Taal told Addison he intended to get some sleep, and that one of the lads would take over in a few hours’ time. Addison said goodnight to the skipper.

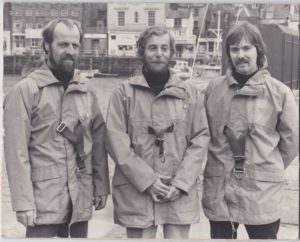

The crew of the Whitby lifeboat White Rose of Yorkshire in 1974. Left to right: Unknown, Alf Hedlam, Pete Thompson (mechanic), Bobby Allen (coxswain) and Dennis Carrick.

Skipper Taal was happy to leave one of his most experienced men at the wheel, and he went to his bunk.

An hour or so later, mate Alan Marston was wakened by a bumping, grinding noise. He could not figure out what it was – it never even crossed his mind that the vessel had hit rocks. She would have to be way off course for that to happen.

Skipper Taal returned to the wheelhouse minutes after the same sounds had awakened him. He could not take in what he was seeing.

Addison was staring blankly, clinging to the wheel as the vessel smashed into the rocks.

“What the hell are you doing?!” Taal shouted. Addison stared straight ahead.

The skipper pushed past to get to the radio and issue a Mayday as water began to come into the wheelhouse.

Alan Marston joined the two men. Addison turned to him, still staring, and in a timid, almost mumbled voice, said: “Oh! Alan!”

Skipper Taal ordered the crew to don their lifejackets. He then tried in vain to anchor the vessel, but she turned broadside and started to fill with water.

Addison, who Taal had pushed aside when he made the SOS call, looked stunned and dazed, and seemed powerless to act.

Bobby Allen, the heroic coxswain of the RNLI lifeboat William and Mary Durham on the night of the tragedy.

Admiral von Tromp was now sinking in thick fog, with a heavy swell breaking on the stern. She began to heel over.

Frankie Taal ordered the crew to hang onto the starboard side, but the seas were too heavy. Waves of 20ft and more battered the vessel.

The desperate crewmen and their skipper returned to the wheelhouse, which was slowly filling with seawater. They were there for an hour.

The wheelhouse continued to fill with water, and the men’s heads banged off the ceiling. They scrambled to an open window – Skipper Taal was last out.

Scotch Jack Addison was dead; he had drowned in the wheelhouse.

It was 3.02am when the distress call reached the Whitby Coastguard saying that the boat was aground under the cliffs in the vicinity of Whitby High Light.

Maroons were fired, and a chain of phone calls was made to alert crewmen to get to the station.

The RNLI Watson-class boat William and Mary Durham slipped her mooring little more than 20 minutes later into an increasingly confused sea.

Coxswain Bobby Allen was in command of the temporary lifeboat, which was there while the port’s regular boat, The White Rose of Yorkshire, was being serviced. Allen set his course southeast by south for the latest reported position of the vessel, ‘in the vicinity of Black Nab rocks’, in Saltwick Bay.

Those rocks were only 350 yards or so from the shore. Later, coastguards reported that the Admiral von Tromp had been 90° off course.

The men of the Whitby ILB crew, led by helmsman Richard Robinson (centre).

In spite of the breaking swell, heavy fog and very poor visibility, Bobby Allen maintained full speed until about 3.50am, when he stopped his engines.

He listened for any activity, and then radioed the stricken vessel to set off some fire flares.

In the loom of lights inshore, he headed in to investigate.

He could see heavy breaking seas smashing across the Admiral Van Tromp. She was lying head southeast on her port bilge, and listing steeply to port.

As Allen tried to move closer, his boat was ‘pooped’ – caught by waves from the stern – by breaking seas. He withdrew full astern.

Men from the Whitby Coastguard fired rocket lines towards the grounded vessel, but the weather was now so bad the crew could not come onto the deck to try to secure them.

Seven times, Allen got his lifeboat near to the stricken vessel and her desperate crew. At one point, the two craft bumped each other.

At 4.14am, Skipper Taal told Allen: “It’s getting desperate!”

Unaware who was still onboard the Admiral von Tromp, Allen decided to anchor his boat some 60ft from her and try to fire three lines, but all were washed away.

The combined crews of the main and inshore Whitby lifeboats in 1976.

Then his own life was put in danger when it became clear the anchor was no longer holding. The lifeboat was now being swept broadside towards the rocks.

In a remarkable display of courageous seamanship, he put his engines on full ahead and wheeled hard to port, clawed the lifeboat head to sea, and cleared her as she started to bounce on the rock shelf.

The anchor was recovered but the fluke had broken off, rendering it useless.

Quick-thinking Bobby Allen took the lifeboat alongside a nearby fishing vessel, Jann Denise, and borrowed her large anchor, as well as a smaller one from another craft, the Courage, from which he also got two line throwing units.

With the new heavy anchor, Allen was able to veer close to the stricken vessel. The brave Whitby coxswain had been battling for almost three hours in raging seas and thick fog.

There was now no sign of life on the Admiral von Tromp as she lay on the rock.

The RNLI boat got within 25ft of the doomed vessel when two enormous waves broke across the lifeboat, sweeping three lifeboatmen off their feet aft.

Crewman Raymond Dent’s scream could not be heard in the gale as he managed to hook his arm around a stanchion to prevent himself going overboard. His shoulder dislocated.

His crewmate Howard Bedford was brought back to his feet by his lifeline, but he was knocked unconscious as his head struck the rails.

With the two men now in the well of the lifeboat, Allen had to think fast. He ordered the anchor line to be cut. He then sped clear through the high seas, and managed to transfer Raymond Dent to the Jann Denise to be taken for treatment at Whitby.

Howard Bedford had recovered consciousness and insisted on staying onboard. Bobby Allen returned to the Admiral von Tromp, but the heavy breaking seas once again swept the lifeboat, damaging the after rails. Its VHF handset was also shattered.

There being no sign of life on the stricken vessel, Allen went back alongside the Courage and waited for daylight and a better chance of seeing more.

The wreck of the Admiral von Tromp, photographed in 1976…

When Raymond Dent was landed for treatment at Whitby at 6.30am, two other RNLI men, Michael Coates and Brian Hodgson, went out on the Jann Denise to join Allen’s boat.

By around 8am, visibility had improved. The lifeboat moved into Saltwick Hole. Allen’s heart sank when he saw what he thought was a body – but it was an empty lifejacket.

A radio message brought better news. Two survivors – Alan Marston and Tony Nicholson – had made it ashore.

But Skipper Taal, Scotch Jack Addison and George Eves were still unaccounted for.

Allen then learned that there was a man on Black Nab rocks. He tried to get there, but could not get closer than 50 yards. Coastguard men were trying to fire a line to the survivor, but to no avail.

Allen decided to anchor his boat and await the inshore lifeboat, which had left Whitby at 8.23am.

The rescue was now in its sixth hour, and there was less than an hour until high tide. There was still a heavy swell. Visibility was still poor, though improving.

The inshore lifeboat helmsman Richard Robinson kept well out to sea as he made for the Black Nab, but fell foul of a line of breaking waves as he manoeuvred the ILB. Only his long experience and expert handling prevented almost certain capsize as he edged inshore.

He was alongside Bobby Allen’s craft by 8.45am – 22 minutes after leaving the shore.

Robinson spotted a man on the rocks, and took the ILB through the confused broken waters into Saltwick Bay.

The man started to clamber over the rocks as giant waves swept across them, and Robinson realised that at any moment the man would be washed away.

… and a year after the tragedy.

He drove the ILB full speed towards the shore. Two of his crewmen, David Wharton and Anthony Easton, grabbed the survivor, skipper Frankie Taal, just as a massive wave broke over the rock.

Miracle was followed by sheer bad luck when the ILB lost power. One of the rocket lines fired earlier had snagged the propeller.

The oars were manned, and as the ILB rose and fell rapidly on the breaking seas, one crewman managed to catch hold of the snagging line and cleared the prop, while another put the anchor over.

The boat continued to rise and fall, but still kept clear of the rock. The engine restarted, and the ILB skimmed over huge waves back to Allen’s lifeboat, which took Frankie Taal safely ashore.

But deckhand George Eves was then confirmed lost, having drowned after he was swept off the roof of the wheelhouse.

Scotch Jack Addison’s body was found weeks later, further up the coast.

Only he knew why the Admiral von Tromp met her fate that night, and the truth of what happened went to his grave with him.

Pierman Walter Sheader, who helped the crew cast off, was later to tell an inquest that there was no trace of alcohol on any of the men he spoke with on that stormy September night. Pathology reports found no trace of drink or drugs in Addison’s body.

The starkest testimony at that November 1976 hearing came from a senior nautical surveyor who said that even if the vessel had been left to her own devices, she would not have gone onto the rocks.

“It really was driven onto the rocks as a deliberate act,” he told the coroner.

In 1977, the RNLI silver medal for gallantry was awarded to coxswain Bobby Allen and the bronze medal to helmsman Richard Robinson. The ‘Thanks of the Institution inscribed on Vellum’ was awarded to second coxswain/motor mechanic Peter Thomson, assistant mechanic Dennis Carrick and crewmembers Howard Bedford, Raymond Dent, Thomas Hansell, David Wharton and Anthony Easton. Medal service certificates were presented to crewmembers Michael Coates and Brian Hodgson.

Photos reproduced by kind permission of the RNLI – with special thanks to Neil Williamson of Whitby Lifeboat Station.

This story was taken from the archives of Fishing News. For more up-to-date and in-depth reports on the UK and Irish commercial fishing sector, subscribe to Fishing News here or buy the latest single issue for just £3.30 here.