David Linkie looks back to a day spent with Shetland skipper Victor Laurenson and crew of the Burra fly-shooter Radiant Star LK 71 in August 2010

Seine-net boats catching a wide selection of whitefish in coastal waters have been an integral part of Shetland’s rich fishing heritage for generations, and nowhere more so than on Burra Isle, two miles west of Scalloway.

01. Radiant Star steaming past Burra light, heading in to Scalloway.

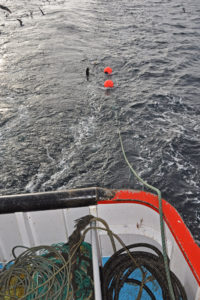

02. Running off the dahn for the first haul…

03. … before the codend is lifted out over the quarter…

04. … as the port wing is shot out of the deck pond…

05. … followed by the starboard wing…

06. … off the elevated net drum.

07. Clipping the starboard rope to the dan leno.

08. Radiant Star turns for the dahn while running the starboard rope.

09. Picking up the dahn.

10. Hauling the first few coils onto the power reels.

11. Radiant Star is hauled astern to the net, when hauling in the last coils.

12. Hauling the wings of the seine-net onto the split net drum…

13. … before lowering the block…

14. … to pick up the taper section.

15. Hauling the extension through the block, while pulling the port wing back off the net drum.

This 2010 trip followed a considerably longer than usual summer break of four weeks, taken due to the shortage of fishing days and whitefish quota – during which time Radiant Star had had her annual refit at Whitby, where the 22.8m vessel had been launched by Parkol Marine Engineering in November 2007.

Few words were spoken while Victor Laurenson drove round Hamnavoe village at 3.30am in the boat’s car to pick up Radiant Star’s crewmen/shareholders. Less than 30 minutes later, the newly painted Radiant Star eased away from the quayside at Scalloway on a spring before entering the main channel. Ten minutes later, the vessel left Burra light astern as skipper Victor Laurenson gradually increased engine power, heading for the Burra Haaf grounds.

Starting little more than 12 miles west of Scalloway, the Burra Haaf grounds are a deep sandy/muddy basin that extends for 10 miles east-west and four miles north-south, varying in depth from 75 fathoms in the middle to 60 fathoms on the edges. Down the years, they have consistently yielded reliable catches of mainly whiting and haddock, together with a general mix of flats and other whitefish, for a large number of Shetland boats, including up to a dozen Burra Isle seiners. Before Hamnavoe pier was built and Burra was connected to the Shetland mainland by road bridge, these were anchored offshore overnight.

Little over an hour later, and after checking the hydraulics, Radiant Star’s dahn disappeared over the port quarter on a fine summer’s morning, before she steamed north at full speed with the tide. With 11 coils of rope shot, Radiant Star turned to port for the last two coils, before the port wing of a traditional clean-ground grassrope seine-net disappeared from a deck pond and the starboard wing came off the elevated split net drum.

When fishing in areas of clean ground like the Burra Haaf, Radiant Star worked a Jackson 900 traditional leaded grassrope seine-net. With 500 8in meshes in the fishing circle and made from thin (2.1mm-diameter) Sapphire yarn for maximum towing and fuel efficiency, the net measured 200ft on the headline and 250ft on the footrope.

For taking fish off harder bottom and ground edges, Radiant Star shot a high-standing hopper seine with 550 8in meshes in the fishing circle, also made from thin Sapphire netting. Chains and wires were rigged on either side of the 150ft of 10/12/14in-diameter hoppers to give a total fishing line length of 230ft. With a 200ft headline, the hopper seine usually gave a headline height in excess of five fathoms.

Both seine-nets were fished in conjunction with 25-fathom split bridles, with 18mm combination warp above the lower rubber legs.

With the dan leno clipped on, the starboard rope was run off before skipper Victor Laurenson took Radiant Star alongside the dahn, before starting to tow south.

Although the dual-frequency Furuno FCV-1100L (50/200kHz) and Simrad EQ44 (38/200kHz) colour sounders were indicating the occasional mark of fish on the bottom, with a good sloosh of ebb tide still running, Victor Laurenson wasn’t hopeful about the first haul. It was viewed more as a stepping stone for getting into position for the next haul, when tidal conditions would be more favourable.

Towing against the tide, with the ropes being hauled tramline-style either side of the wheelhouse – skipper Victor Laurenson’s preferred option – Radiant Star was covering the ground at 0.9 knots, with the Mitsubishi propulsion engine running at a highly economical 750rpm.

It was therefore something of a surprise when, 90 minutes later, after the wings of the net had been taken onto the split net drum as the bag was hauled through the block and flaked down to starboard, a healthy-looking codend came towards Radiant Star’s quarter. Minutes later, the first of three lifts was taken aboard using the 10t codend Gilson and released into the reception hopper. With the codline quickly retied, the codend was lowered back into the water, before the remaining fish were split for a second time.

Having expected mainly whiting and haddock, the presence of a good sprinkling of green, together with some flats and the odd monk, added to the surprise outcome.

Skipper Alan Umphray called Victor Laurenson up on the VHF to report taking a slack lift of similar fish on the Scalloway seiner Valhalla, which had shot one berth to the east. A burst hydraulic hose had delayed hauling, with a negative impact on the tow.

Within a couple of minutes of the codend being returned to Radiant Star’s starboard quarter, the dahn was disappearing astern against the distinctive profile of Foula, some 10 miles to the north. Radiant Star ran off the port rope into the SSW in preparation for taking the second haul into the first of the flood, in one of Victor Laurenson’s favourite and often-used sets.

With the hopper half full, the crew had their work cut out to get the contents gutted and boxed in the fishroom before the next haul. The efficiency of Radiant Star’s fish-handling system, supplied by Michael Pottinger of Scalloway, quickly became apparent, as a conveyor took fish forward from the base of the hopper to the four crewmen standing in line to select and gut the first haul.

The four main selections of fish were put into one of four tiered troughs that sloped gently downwards to the central washer. Less frequent selections were placed in seven bins arranged above the longer troughs. On being released from the various divisions, the force of water circulating through the washer eased the fish out onto a second shorter elevated conveyor running forward, from which fish descended via a delivery tube onto a selection table in the fishroom.

Shortly before skipper Victor Laurenson called the crew to stand by aft for the net coming up, Marvin Inkster had followed Jimmy Reid up the fishroom ladder, after 40 boxes of fish had been weighed on a set of Marel M2200 electronic scales linked to an Intermec label printer, boxed and iced. A quick glance at the fishroom working tally showed that the 24 boxes of green included six of medium, eight of selected and nine of small, highlighting the fact that a number of different year classes were evenly represented.

As the codend came to the surface again, to reveal a second successive splitter with green the dominant species, an increasingly worried frown developed on Victor Laurenson’s face, followed by the comment: “Regardless of whatever else happens today, we need to change the game plan tomorrow, as one thing is certain – we can’t come back here again too soon.”

The reason for this was that in taking what turned out to be 94 boxes of green, after being at sea for just 15 hours, Radiant Star had virtually taken its two-monthly allocation of cod quota from the Shetland PO. This was a stark reminder of the problems skippers were facing at the time – and continued to experience for the next 10 years and counting – due to the ongoing imbalance between stock levels and quotas.

For the four weeks after this trip, Radiant Star fished a combination of one- and two-day trips in such areas as the Ve Skerries, Foula and St Magnus Bay west of Shetland, and south to Fair Isle, three or four days each week, before landing a wide mix of whitefish that included a good percentage of skate, haddock and whiting, and minimal quantities of cod.

With their first two hauls after several weeks ashore proving successful, the crew were in buoyant spirits as Ian Couper lowered the block almost to deck level to pick up the taper for the third time that morning. However, as is invariably the case, fishing can never be relied on to run smoothly for too long. After the absence of the codend on the surface had raised concerns, two boulders were left lying in the stone trap after a slack lift of fish was released. Fortunately, damage to the net was relatively small, enabling repairs to be implemented as the port rope ran off again.

On the plus side, the reduced number of fish in the hopper finally allowed the crew to grab a well-deserved mug of tea and bacon roll.

After Radiant Star had steamed a couple of miles into the southwest to deepen the water and move onto the sandier bottom of the Scalloway Deeps – while opening up Fitful Head to reveal a distant Sumburgh, the southernmost point of Shetland – the dahn was dropped astern for the fourth shot.

This, like the subsequent fifth haul, yielded around 18 boxes, including a higher percentage of whiting and a couple of boxes of higher-value monks and megrim, as the fishroom took on an increasingly healthy appearance in the early afternoon.

As a result, rather than taking the seven hauls expected 12 hours earlier at the start of the day, skipper Victor Laurenson decided that six would be enough, before steaming a few miles east for the final shot, thereby shortening the distance back to Scalloway.

Shortly after a fine supper of fried whiting, chips and peas had been enjoyed, an uneventful last haul resulted in another 21 boxes of fish being transferred to the fishroom – plus a large common skate, which was immediately helped over the side of Radiant Star’s shelterdeck before, with a couple of grateful flicks of its wings, it started to swim back to the seabed.

Shortly after 6pm, skipper Victor Laurenson set an ENE course on the Navitron autopilot for Scalloway, some 10 miles away, after making a quick detour towards Valhalla, which was just starting to haul her net in the adjoining seine-net shot a mile to the south.

By 8pm, Radiant Star’s crew had landed 143 boxes of top-quality seine-net fish caught in the previous 12 hours into the refrigerated fishmarket at Scalloway. The mixed shot included 94 boxes of cod (six boxes of A2s, 25 boxes of A3s, 28 boxes of A4s and 33 boxes of A5s), 22 boxes of whiting, 16 boxes of haddock, four each of plaice and megs, and three each of monks and lemons. The following morning, the catch, together with Valhalla’s fish, was bought remotely by local fish merchants at Lerwick, sitting in front of the electronic auction clock operated by Shetland Seafood Auctions.

With only one other Shetland vessel landing at Lerwick, Radiant Star’s cod sold at £2.15-£2.95 per kg, whiting £1.63-£2.10, haddock £1.30-£2.67, monks £2.65-£4.56 and megs £3.50-£4.15.

In the 10 years following this trip, Radiant Star has continued to perform consistently well, following the skipper and crew’s longstanding pattern of fishing locally around Shetland, and whenever possible finishing up on a Thursday night for the weekend.

Computerised fly-shooting

Radiant Star was custom-designed for seine-netting using powered rope reels which, in addition to having a core pull rating of 15t, have a usual working capacity of 16 coils of 36mm-diameter seine rope.

Radiant Star was only the second seine-net boat in Scotland to be equipped with power reels rather than a conventional seine-net winch and rope storage reels. The first was Lossiemouth skipper Alasdair Milne’s 23.99m Tranquility INS 35, built by Miller (Methil) Ltd in 2001.

That power reels are now a standard feature on new fly-shooters is testament to the foresight shown by the skippers and suppliers at the time Tranquility and Radiant Star were built.

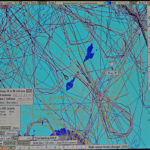

Manufactured by Thistle Marine of Peterhead, the power reels are located forward on the main deck and controlled from the wheelhouse using a Scantrol Ispool computerised auto-seine system.

Ispool provides a constant display of hauling speed, hydraulic pressure, tension, rope length, and the differential between port and starboard warps. When the selected differential is exceeded, the reel for the longer rope is automatically slowed down before reverting to the chosen rate. The system also caters for four modes of operation – towing, stopped, heaving and shooting. When shooting away the ropes, the main motor is disengaged, and the winch reels are allowed to freewheel, with a smaller hydraulic motor being fitted for braking purposes.

The hauling speed can be infinitely varied, from 10m per minute when first creeping back the gear on the first coil, to 280m per minute – more than a coil per minute – when the net is closed off, with four to five coils of rope in.

The efficiency of the system was shown by the fact that as the last few coils were whipped aboard, Radiant Star was pulled back to the net at up to four knots.

Together with the increased shooting speed, this generated a saving of 10 to 15 minutes on a typical seine-net drag, which previously took two hours.

A further benefit provided by the power reels is the extended life of the ropes, because the amount of sand abrasion and wear is reduced by not being continually hauled over the smaller-diameter barrel of a traditional seine-net winch.

Working two continuous four-coil runs of 36mm-diameter Itsaskorda seine-net rope either side of a similar five-coil length, skipper Victor Laurenson reported a lifespan of two to three years for the middle section, and some 15 months for those on the ends.

By working a port dahn and a starboard bag, the port rope is over-ended each haul, while the starboard rope is turned occasionally by dahning off the starboard side.

Whitby-built Radiant Star

Built at Whitby in 2008 to an SC McAllister design, the 22.8m Radiant Star had the distinction of being the biggest boat to date built by Parkol Marine Engineering.

Radiant Star was also of particular significance for Shetland, as it was the islands’ first new seine-net vessel for nearly 20 years, the previous one being John Scott’s Telestar LK 378, built by Jones of Buckie as the last in a succession of dual-purpose whitefish trawlers with seine-net capability built for Shetland skippers in the mid-1980s.

With an LOA of 23m and a beam of 7.2m, Radiant Star is powered by a box-cooled Mitsubishi S6R2 MPTKF engine, which is dedicated to propulsion duties apart from a net-retrieve system driven from the fore end. The propulsion unit develops 479kW @ 1,350rpm and is coupled to a Reintjes 7.46:1 reduction gearbox to turn a Lips 1,900mm-diameter propeller in a matching Lips HR propulsion nozzle.

Using a TechnoDrive splitter box and two double pumps, the seiner’s main hydraulic system is driven from the flywheel end of a Cummins QSM11 auxiliary mounted on the starboard tank top. Developing 264kW @ 1,500rpm, the electronic Cummins auxiliary also drives a 75kVA Mecc Alte 415/3/50 generator from the fore end, in addition to a 155amp 24V Transmotor.

A similarly rated generator is driven by the smaller Cummins 6BT auxiliary engine, in addition to a second belt-driven 24V DG 155 Transmotor generator for battery charging duties and the hydraulics for the landing crane.

Since entering service, Radiant Star had returned a highly economical level of fuel consumption, with which the owners were fully satisfied.

When making four hauls during the short winter days, usually within 40 miles of port, the seine-netter typically used less than 800 litres. Even when taking up to nine hauls during the long summer days, the amount of fuel used seldom, if ever, exceeded 1,200 litres, giving an approximate average of 60 litres per hour, and a top speed of 11 knots.