In 1980, young photographer Alec Gill was invited to document a mackerel trip off the South West coast onboard Cordella H 177. Forty years on, he recalls the memories evoked by his pictures

Deep-sea mission

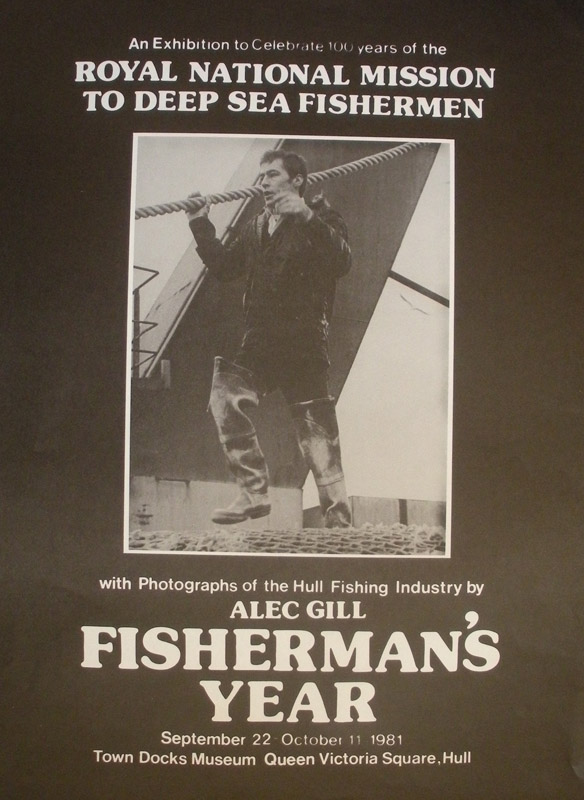

My camera is a passport into many places and situations. In November 1980, it took me aboard the Hull trawler Cordella. It was a welcome (unpaid) commission from the Royal National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen. George Gilmour was the Hull superintendent, and he wanted a photo exhibition to mark the Mission’s centenary the following year.

My camera is a passport into many places and situations. In November 1980, it took me aboard the Hull trawler Cordella. It was a welcome (unpaid) commission from the Royal National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen. George Gilmour was the Hull superintendent, and he wanted a photo exhibition to mark the Mission’s centenary the following year.

He must have seen my first two photo exhibitions, about the kids, and the elderly, of the port’s Hessle Road fishing community. George was a gentle and thoughtful Scottish chap. We hit it off straightaway. He made the arrangements with trawler owner J Marr & Son. All I had to do was turn up at Falmouth Docks on 24 November for the start of a mackerel fishing trip off the South West coast, into the Celtic Sea around Wolf Rock.

Falmouth was not too difficult to get to, as I was then based in Cardiff conducting my postgraduate psychology research. I hired a car with my Singapore friend Chay, we drove down into Cornwall, and he saw me onboard with my equipment. My Rolleicord twin-lens reflex camera opened the door into an adventure aboard a deep-sea trawler.

Hunter

Despite physical limitations and some setbacks, I feel I have had a very lucky life. I was extremely lucky to have Dickie Taylor as skipper of the Cordella. We became good friends, and years later he told me how he kept an eye on me as I clambered up and down the ship’s rigging taking photographs of the crewmen at work.

Despite physical limitations and some setbacks, I feel I have had a very lucky life. I was extremely lucky to have Dickie Taylor as skipper of the Cordella. We became good friends, and years later he told me how he kept an eye on me as I clambered up and down the ship’s rigging taking photographs of the crewmen at work.

I am a poor swimmer, so had I gone overboard, I would not have lasted long! Actually, I am not sure I had any insurance – I certainly didn’t pay anything. I dread to think what might have happened had I fallen and hit the deck. I felt at home aboard the ship, and the crew soon accepted me being around. Indeed, it was a good sign when they ignored me, got on with their work and forgot I was taking pictures.

Dickie Taylor’s crew were loyal to him. He was ‘a man’s man’. His proud nickname was the Old Fox – meaning he had an instinct of where to find the fish. He had a deep, gravelly Hull accent.

I was on the bridge one midnight when the newscaster announced that Her Majesty the Queen was making a royal visit to Falmouth on 28 November. From a lock-up cupboard, Dick produced a couple of glasses and a bottle of brandy. We drank to her health and long life.

Teamwork

This picture of the deck crewmen preparing the nets, trawl doors and bobbins for the first shot of the trip shows the complexity of the whole operation. Assembling the trawl gear was a highly organised and skilled task. Any error could prove very expensive, and might jeopardise the whole trip.

This picture of the deck crewmen preparing the nets, trawl doors and bobbins for the first shot of the trip shows the complexity of the whole operation. Assembling the trawl gear was a highly organised and skilled task. Any error could prove very expensive, and might jeopardise the whole trip.

It made my blood boil when the trawlermen were classified as ‘casual labourers’. That erroneous labelling denied them financial compensation as the fishing industry declined during the 1980s and 1990s.

Fortunately, the Hull men had a long-term campaigner in Ron Bateman. He was later supported by Alan Johnson MP. Justice was eventually achieved in 2000 after a long legal battle, assisted by local lawyer Humphrey Forrest – but many fishermen had died before Britain caught up with Europe in financially compensating the redundant men.

Tyne-built

The 70m Cordella H 177 was built in 1973 at the Willington Quay yard of Clelands Shipbuilding Co Ltd of Wallsend, for J Marr & Son Ltd of Hull. The picture on the left shows her in pristine condition in Hull’s Albert Dock in June 1978, while the one on the right was taken during my 1980 trip.

The 70m Cordella H 177 was built in 1973 at the Willington Quay yard of Clelands Shipbuilding Co Ltd of Wallsend, for J Marr & Son Ltd of Hull. The picture on the left shows her in pristine condition in Hull’s Albert Dock in June 1978, while the one on the right was taken during my 1980 trip.

In 1982, she was converted into a minesweeper for service in the Falklands and commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Cordella – but when hostilities ended she was returned to her Hull owner and resumed fishing.

She was later sold to New Zealand, although she returned to Hull in the 1990s. Renamed Olga in 2000, she was subsequently sold to Dominica and renamed Gideon. Sadly, she sank off Newfoundland in May 2006. At least she went down fighting, or at least fishing to the end of her days – far better than in a scrapyard on some foreign shore.

Friendship

Friendship comes in many shapes and sizes. Skipper Dickie Taylor had his regulars amongst the crew, and within those were bonds of friendship. Here are Dick Fowles (nicknamed Suttie) and Roy McGlauglin (Big Mac) taking a break and having a cig between hauls.

Friendship comes in many shapes and sizes. Skipper Dickie Taylor had his regulars amongst the crew, and within those were bonds of friendship. Here are Dick Fowles (nicknamed Suttie) and Roy McGlauglin (Big Mac) taking a break and having a cig between hauls.

It is worth noting that their clothing was not exactly ideal for maritime conditions: an old anorak and a tatty fur-collared coat tied with string. Does this reflect the fact that trawlermen had to pay for and provide their own seagoing clothing?

As a little chap myself, I often had a taller ‘minder’ during my schooldays – a bigger lad would take me under his wing. It was useful when any burly kid made threats, as happened once in junior school. A bully pinned me against the wall and was shouting the odds. I looked at him and said: “I’ll get the Williams brothers on to you.” It was a joy to see the blood drain from his face as he let me go.

Big bag

This haul of mackerel is roughly 30t. It seemed pretty large to me – but I was soon told it was below average. The maximum could be 60t – only then was it classed as a ‘big bag’.

This haul of mackerel is roughly 30t. It seemed pretty large to me – but I was soon told it was below average. The maximum could be 60t – only then was it classed as a ‘big bag’.

One day in the wheelhouse, when the Old Fox saw a medium-sized catch, he turned to me and paraphrased Shakespeare: “Poor but content is rich enough” (Othello, Act 3, Scene 3). Many a time since that day, I have repeated this quote.

In this photo, the bag is being secured on top by junior bosun Tony Wainman and deckhand George Palmer. Everything had to be prepared prior to the large stern hatch being opened, before the fish could be tipped down into the factory level below for sorting and freezing.

I remember being alongside a bag of mackerel as it was being hauled from the seabed. As the water gushed out of the net and rushed past near the top of my wellington boots, I noticed that it was red. I naively assumed it was rust from the Cordella. “Oh no,” a nearby crewman told me. “It’s blood.”

Plenty of packing

The Old Fox was of the opinion that the second most important man aboard a trawler was the cook. The deckhands worked very hard, used up lots of energy and needed good grub to keep them going. This was especially the case when the fish was gutted on the open deck and the men were exposed to the elements. If the cook served up rubbish food, the crew became unhappy – and an unhappy crew resulted in a bad trip for everyone.

The Old Fox was of the opinion that the second most important man aboard a trawler was the cook. The deckhands worked very hard, used up lots of energy and needed good grub to keep them going. This was especially the case when the fish was gutted on the open deck and the men were exposed to the elements. If the cook served up rubbish food, the crew became unhappy – and an unhappy crew resulted in a bad trip for everyone.

The head cook on the Cordella was Chalkie (left in this picture – I never did establish his full name), with assistant Arthur Cowley in the galley. A cook was sometimes nicknamed a ‘pan artist’ or ‘dusty miller’. The latter was probably because they got covered in flour when baking bread. I wonder if that is how ‘Chalkie’ got his name.

One of the first questions Skipper Taylor asked me was: “Who do you want to eat with – the crew or the officers [himself, the mate, the wireless operator and the engineers]?” Straightaway I said: “The crew.” They were going to be my primary photographic subjects, and I did not want to appear aloof. You only really get to know someone when you break bread with them.

If I got seasick, sympathetic crewmen told me: “Get plenty of packing down yer!” This meant the cook’s bread – well, it was a good excuse to have more. The Cordella bread was delicious.

Salt of the earth

Of all the Cordella crewmen, I particularly took to George Palmer. This is him overseeing the fish-freezing process in the ship’s factory (the young lad watching the job is Graham Lee). George had a relaxed outlook on life and a fair share of wisdom.

Of all the Cordella crewmen, I particularly took to George Palmer. This is him overseeing the fish-freezing process in the ship’s factory (the young lad watching the job is Graham Lee). George had a relaxed outlook on life and a fair share of wisdom.

I kept in touch with George after the Cordella trip, and was keen to interview him when filming my DVD ‘Arctic Trawlermen: Last of the Hunters’ (available via Amazon). Ideally, I would also have included the Old Fox, but I had already filmed Dick on an earlier DVD (‘Fishing Families of Hull’) and had a strict policy of never using the same person twice.

George was a brilliant Hessle Roader – a genuine, salt of the earth, loyal and friendly bloke. He is perhaps the embodiment of why I have kept going with my dedicated photography, research and writing about Hull’s fishing community for 50 years – I began in 1971.

Assembly line

The camera unwittingly captures history before our eyes, even if the photographer is unaware. Only the benefit of hindsight lets us see things anew.

The camera unwittingly captures history before our eyes, even if the photographer is unaware. Only the benefit of hindsight lets us see things anew.

With the advent of the 1980s, freezing fish at sea was a new technique being adopted within the trawling industry. I did not realise it at the time, but it was good to document this process as it evolved. This is Tony Wainman, then a junior bosun, who later moved up the hierarchy at sea.

Tony was on the quiet side, but worked hard and was respected by the rest of the crew for his diligence. Like the majority onboard, he smoked, and was often seen with a fag in his mouth. It was, after all, hard and stressful work. It seems, however, that food hygiene was not high on the agenda aboard – but that was four decades ago.

Comradeship

Harmony within most organisations usually stems from the top down. I believe the happy Cordella crew was due to the skipper. I do not recall how this ‘posed’ picture came about, but it shows the comradeship onboard. These four men – Roy McGlauglin, George Palmer, Mike Lamb and Norman Whitely – are stood behind the hoist wires that lowered the 20kg frozen boxes of mackerel from the factory level down into the ‘dead house’ freezer section.

Harmony within most organisations usually stems from the top down. I believe the happy Cordella crew was due to the skipper. I do not recall how this ‘posed’ picture came about, but it shows the comradeship onboard. These four men – Roy McGlauglin, George Palmer, Mike Lamb and Norman Whitely – are stood behind the hoist wires that lowered the 20kg frozen boxes of mackerel from the factory level down into the ‘dead house’ freezer section.

I really felt looked after by all the crew members – had anything gone wrong, they would have made sure I was safe – though as nothing untoward happened, this is totally hypothetical. Nevertheless, it is a good feeling to look back on, and this photo captures that sentiment.

Next generation

Time and tide wait for no one, and trades too can fade into the past. Although my home port of Hull now has no fishing industry left, back in 1980 there was still a good enough infrastructure for it to continue – had circumstances not contrived against it.

Time and tide wait for no one, and trades too can fade into the past. Although my home port of Hull now has no fishing industry left, back in 1980 there was still a good enough infrastructure for it to continue – had circumstances not contrived against it.

Each occupation depends upon a new generation entering its ranks in order for it to survive. This was certainly the healthy situation when I was taking photographs on the Cordella. There were four ‘deckie learners’ aboard.

Here we see young Gary Colby laughing and happy in his work – fitting in well as a newcomer with the crew. He is working on the assembly line in the ship’s factory deck. The 20kg blocks of mackerel have been frozen and are being wrapped in polythene bags before being boxed up for storage.

Over 40 years later, Gary and I are still in touch, via Facebook, even though he now lives and works in Thailand, with his wife and young daughter. I was able to double-check some of the crewmen’s names thanks to the wonders of the internet.

Oil and water

A nautical saying is that ‘oil and water do not mix’, and it sometimes applied at the human level too. That is, a chief engineer and a skipper sometimes had disagreements. If it was a poor trip, the skipper might blame the engineer for breakdowns or not producing enough speed on demand. Equally, the engineer might grumble that the skipper was inadequate in his fish-catching abilities. Not that this happened during my trip.

A nautical saying is that ‘oil and water do not mix’, and it sometimes applied at the human level too. That is, a chief engineer and a skipper sometimes had disagreements. If it was a poor trip, the skipper might blame the engineer for breakdowns or not producing enough speed on demand. Equally, the engineer might grumble that the skipper was inadequate in his fish-catching abilities. Not that this happened during my trip.

This is chief engineer Michael Baldwin, wearing headphones in the noisy environment and concentrating intently on some mechanical problem.

I did not go down into the engineroom more than this once. It was extremely noisy, hot, cramped and impossible to talk. I felt I was getting in the way of the work. Added to that, it was a precarious operation clambering down the steps with my camera swinging around my neck, and I was not dressed properly to be amongst the dangerous machinery.

Sparks

Technology and trawling go hand in hand. After the Second World War, fishing would have been difficult without a radio operator onboard. Few people in the industry used this official title. In Hull, at least, operators were called ‘sparks’.

Technology and trawling go hand in hand. After the Second World War, fishing would have been difficult without a radio operator onboard. Few people in the industry used this official title. In Hull, at least, operators were called ‘sparks’.

In the earliest days (around 1913), trawler owners installed a wireless for financial rather than safety reasons. The equipment was so basic it was liable to spark away.

This sparks is John Green. I did not get to know him very well – but he must have been good, because Skipper Taylor mentioned how a sparks was worth his weight in gold if the two of them worked closely together. Part of the sparks’ job was to carefully listen in to what other skippers were saying to their friends on nearby trawlers, pick up on who was ‘on the fish’, and let his skipper know.

Dead house

They say ‘the price of fish is paid in men’s lives’. The hidden price-tag can also include long-term ill-health. This photo shows the boxes upon boxes of frozen mackerel in the dead house. This was the trawlermen’s name for the cavernous deep-freeze section of the Cordella, because that is where all the fish was stored, frozen stiff – like corpses in a morgue, I suppose!

They say ‘the price of fish is paid in men’s lives’. The hidden price-tag can also include long-term ill-health. This photo shows the boxes upon boxes of frozen mackerel in the dead house. This was the trawlermen’s name for the cavernous deep-freeze section of the Cordella, because that is where all the fish was stored, frozen stiff – like corpses in a morgue, I suppose!

On the left is Darryl Taylor, the factory manager and son of Skipper Taylor. Working in such sub-zero conditions was harsh, and took a toll on the body and mind. The -22ºC temperature was maintained by what the crewmen called trike (trichloroethylene or TCE, invented by ICI) – a freezing liquid gas used in industrial refrigeration units.

The crewmen profoundly disliked being down in the dead house for too long. Some got really bad burns, lung problems, dizziness and headaches when unwittingly inhaling gas from leaking pipes. I only found this out whilst writing this text. Ignorance is bliss! Or should that be ‘more fool me’?

Pleasure trip

During the 1960s and 1970s, I hitch-hiked around Europe and the Near East. In a convoluted sense, I was hitching another ride on the Cordella.

During the 1960s and 1970s, I hitch-hiked around Europe and the Near East. In a convoluted sense, I was hitching another ride on the Cordella.

Anyone aboard a trawler who did not contribute one way or another towards catching fish was considered to be on a ‘pleasure trip’. That was certainly me as a photographer aboard the Cordella.

I found that there were only so many images that could be captured of the men at work and life at sea. Added to that, in the pre-digital age, there was a limit to how many 12-image rolls of film I could carry in my luggage. So after about 10 days, it was time for me to go back to Wales and my psychology research.

Skipper Dickie Taylor easily arranged for the Falmouth pilot vessel to come and get me. I felt sad to leave this battered-looking Hull trawler. I still feel a deep, sentimental attachment to the Cordella – she looked after me at sea.

Centenary exhibition

All good things come to an end. My adventure with the Cordella concluded with a photography show.

All good things come to an end. My adventure with the Cordella concluded with a photography show.

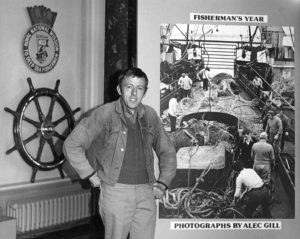

This is me at the Fishermen’s Mission exhibition in autumn 1981 at Hull’s Town Docks Museum (now renamed the Maritime Museum). Officially, it was entitled ‘Fishermen’s Year’ – but someone made a spelling mistake and called it ‘Fisherman’s Year’, as if there was only one man being fêted!

What I especially liked was that a fair number of Cordella’s crew happened to land in Hull during the show, and I met up with them. We looked around the gallery together and recalled the trip. I regret not taking a photo of them there at the time.

Although I was based in Wales during 1981, it was a busy year for me with five exhibitions: three in Hull and two in Tennessee. When this photo was taken, I still had some remnants of my suntan from the States. Exhibitions are a lot of fun, but hard work. Once they are over it is like switching off a light – the event is soon forgotten by the public and media. A book is better – like a longer-lasting exhibition. I hope this set of photographs conveys just a hint of my wonderful voyage aboard the Cordella.

Klondyking

I was keen to take photographs in Cordella’s ‘dead house’ – but the crew warned me I would not last long down there. That was true, and my Rolleicord camera was none too happy either. This is Ian Beal transferring frozen boxes from the hoist to be stacked in the enormous freezer.

I was keen to take photographs in Cordella’s ‘dead house’ – but the crew warned me I would not last long down there. That was true, and my Rolleicord camera was none too happy either. This is Ian Beal transferring frozen boxes from the hoist to be stacked in the enormous freezer.

Whilst I was onboard, there were several other Hull trawlers also catching mackerel. Most of them were ‘klondyking’. That is, British vessels caught the fish and then transferred the whole lot over to giant factory ships belonging to Soviet and Eastern Bloc countries.

The Cordella’s catch, however, was handled differently. The fish was frozen in these boxed blocks and stored ashore for sale at a later date – maybe when the price was higher. I did wish, however, that we had done klondyking from a photographic point of view. It would have been exciting to get up close to those vast foreign vessels, with their ring of old rubber tyres around the hulls. The tyres were to minimise damage to the British ships during the tricky transfer of the fish in choppy waters at close quarters.